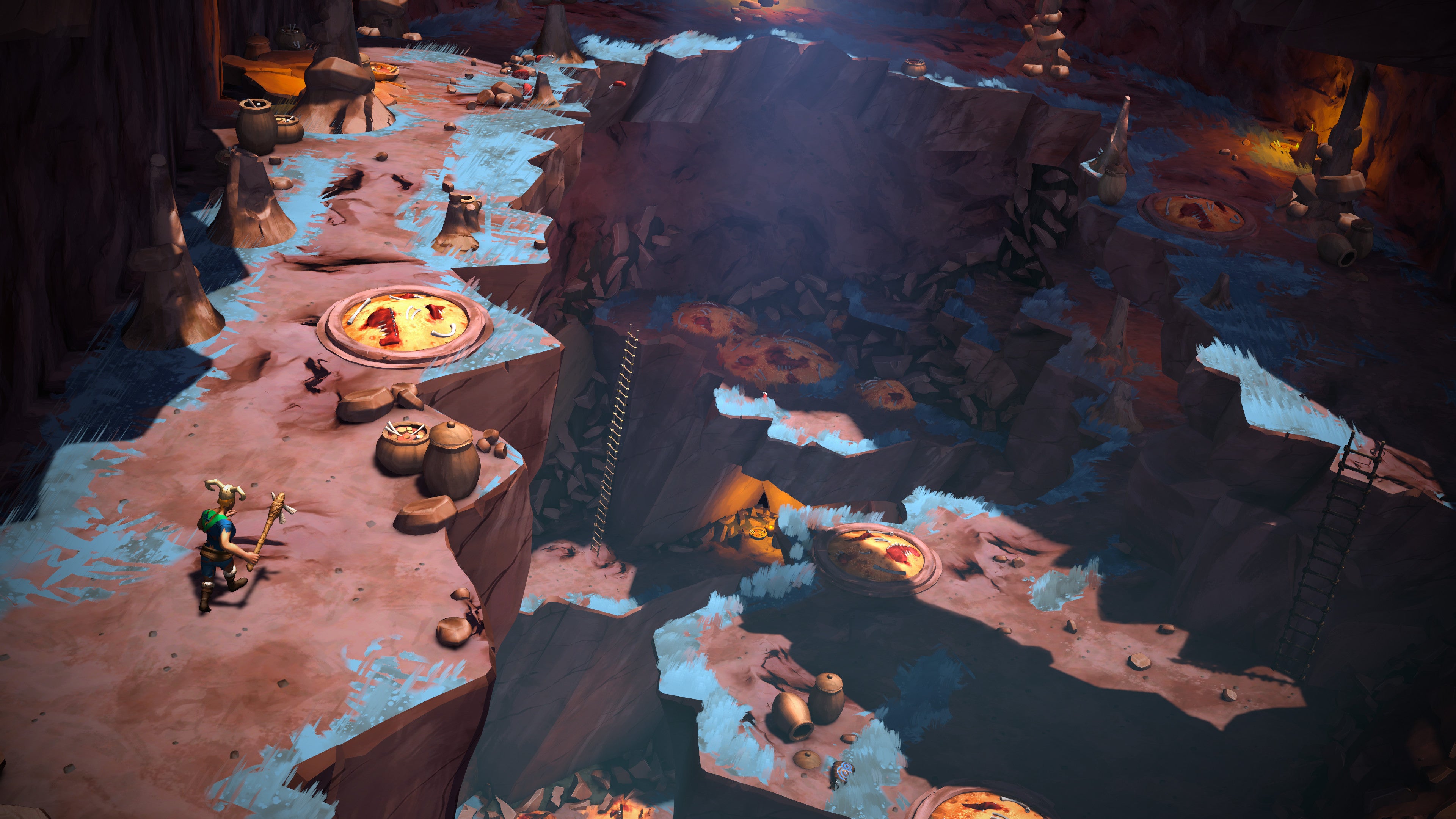

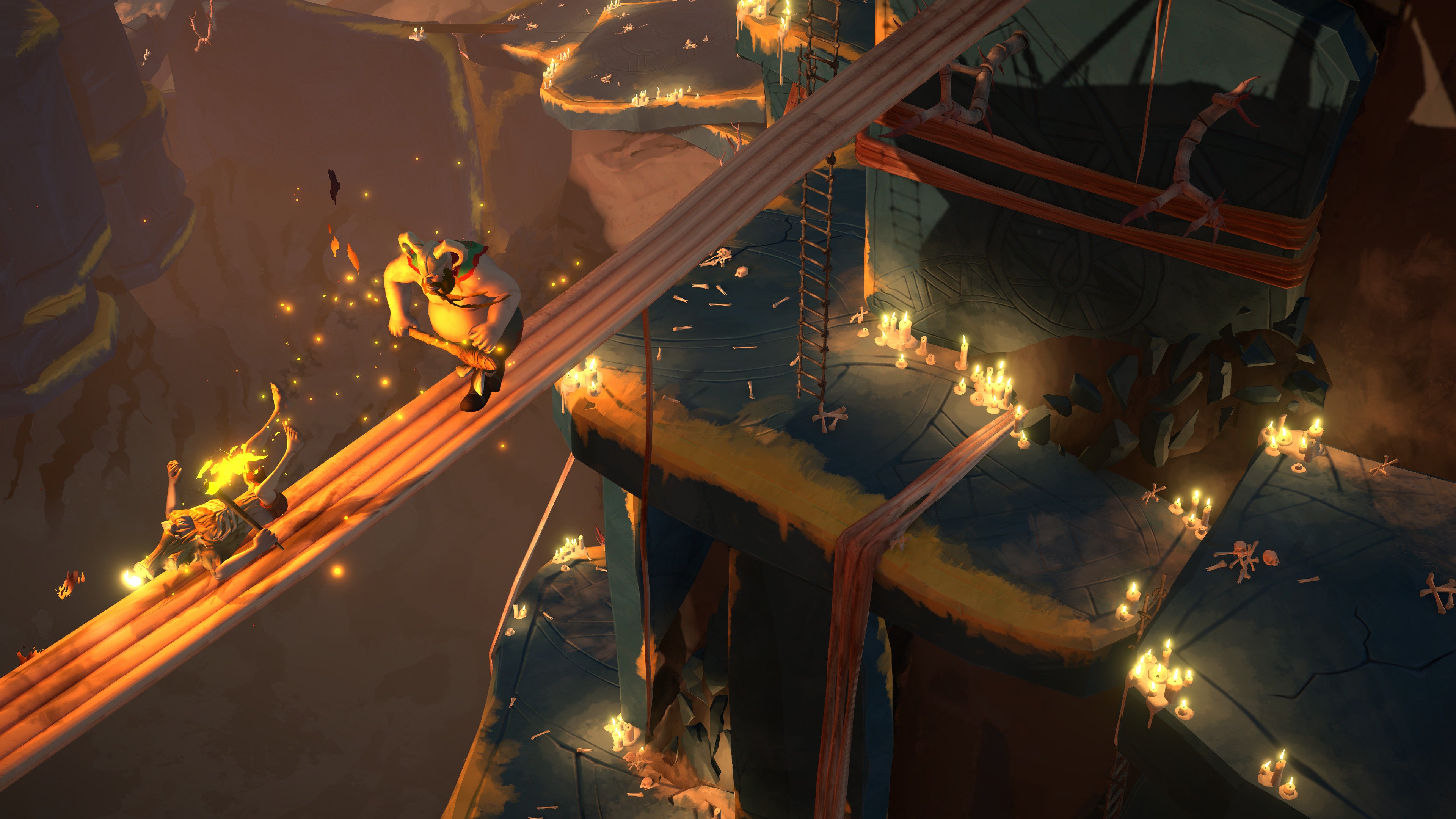

This is a special game. I am horrible at it, and it, in turn, is horrible to me, and yet I keep pushing on, returning to Gods Will Fall again and again. What first seemed like a muddle of odd ideas has resolved itself into one of the most promising things to happen to roguelikes and Soulslikes in an absolute age. Lochlannarg has earned that lightning, if you ask me. And that bath. I am tempted to slice up some cucumber for them. This is the story of eight friends who decide to kill a bunch of gods. A celtic gang up against a range of gaping monsters. The reason for this is pretty simple - the gods are depraved and wretched and awful. Skeleton spiders and cabbage-winged moths with bony spiked tails, horror creatures, each apparently uncertain whether to dress for a day spent as animal, vegetable or mineral, and each sat at the center of a shifting dungeon of grimness and death. The friends are procedurally scrambled each time you start afresh, and they’re dropped on an island that is home to ten gods, all in need of an almighty shoeing. The island itself is beautiful in its windswept craggininess, rounded barrows and stone doorways, chilly beaches and tunnels of worked stone. The doors all give a hint of the ghastly creature that lies behind them. It is a stern challenge. The eight celtic warriors you control are eight lives, in essence, each with their own starting traits and weapon. You choose one - a heavy, slow guy with an axe, maybe - and you choose a doorway with a god beyond it. Then you go in and you and the heavy slow guy with the axe try to get as far as you can, and hopefully fell the god. If you do, then that’s one down, nine to go. If you don’t, the heavy guy is now trapped in there, and will only be released when someone does fell the god - and maybe not even then. All your crew trapped? Game over. A couple of things. Firstly, I love the fact that the game dwells on the rabble dynamics. When you choose a warrior to go in, they might work their shoulders or bellow with confidence before dashing towards the dark interior, and their friends will cheer them on. When the door opens after a run and it’s victory, expect a bit of theatrical bowing, a bit of mock-dandyism. When the door opens and nobody emerges? There is proper wailing. Renting of garments, heavy bodies sagging to the ground in disbelief and despair. I have never really seen this sort of thing in a game before. Sure, this system ties up a thicket of stats - maybe the missing party member gives a remaining warrior a stat drop out of fear, or a boost out of anger! But it’s also just interesting to see: it gives you more of a position in the market, as they say on Wall Street. It makes you care a little more, and hate the gods a little more. Secondly, getting to the god in the first place is no picnic. Picnics are definitely not part of this game. Each god’s lair is themed around their horrible nature, and each lair will be crawling with enemies. Take the enemies down, and you weaken the god - you can see their life bar being chipped away as you hack foes to pieces en route - but even that isn’t easy. The simplest foe can do a lot of damage if you give them an opening. So what do you do? Take ’em on and weaken the god, or preserve your health and stealth your way to a more deadly boss encounter? Combat sings here. Whatever the stats on your warrior, whether they are carrying a mace or a sword or a pike or something else, there is a weight and deliberation to light and heavy attacks that will be familiar to anybody who’s played Dark Souls. A flurry of light attacks might seem like a good bet, but just one counter can properly wound you. Depths beckon. A flash of light from a foe is a tell that they’re about to strike, so you can parry by dashing straight into them - a move so simple and direct it requires genuine bravery the first few times you do it. Down them and you can do a ground-pound, if you get the positioning right. Kill them and you may be able to grab their weapon and chuck it into someone else - the sense of collision is wonderfully cruel and comic. Aside from a gentle nudging when you’re aiming a throw, there’s no explicit lock-on here, and its absence works boozy wonders. It gifts each encounter the inelegant windmilling brutality of a pub brawl - all gristle and flailing misses. For all its fantasy, Gods Will Fall can feel very real. This all matters because combat ties into your well-being - yet more risk and reward. Lay on attacks and you build bloodlust, which can be converted back to health with a roar move. So each encounter really makes you think a bit - and the lower on health you may be, the more willing to take risks you might become. All the way through to the boss! It’s not just combat, there is a genuinely creepy sense of exploration as you pick your way through these godly palaces. One might be an endless river, cockle-shells as doors and rusty grass. My favourite is a sort of warrior’s blacksmith gaff, pools of sparking red flame glimmering in the darkness, forges where you might improve a weapon if luck is with you, occasional doorways to the outside world where the sun is blinding and the wind is picking up. From the fungal battlements and thick ropes of Breith-Dorcha to the rotting boatyards of Boadannu, locations are evoked with an art style that makes the rocks and stones feel hand-crafted, that flings seaweed with poise, and offers a little chilly grandeur, off-set neatly by the Bash Street Kids gaggle of Celts you’re controlling - all chins and elbows and spindly legs. The camera has a gentle buck and sway to it at times, making your adventures feel even more illicit somehow, an observer watching from afar with interest. The developers know when to move the camera in a touch so - yes! - that enemy is wearing part of a boat as armour, and when to pull the camera out to show bleached rock and stunted bonfires stretching into the distance, this moon shot, this Venusian tundra. The gods themselves can be a brutal challenge. And yet sometimes, they can be a knockover. This is another of Gods Will Falls’ big ideas - random difficulty, ramping up one god on one run, and squishing them down the next. This is designed to encourage replayability, but it can make your first moments with the game deeply unforgiving. I love the sense of surprise it lends to each run, the sense of time passing and things changing, but it has warped the way I play at times, encouraging me to lead with my least promising warriors, sending the most useless on speculative trips into the depths just to see what kind of fate awaits them. Ultimately, part of the game is concerned with trying to get your luck to line up with the game’s regular scrambling of the odds. It’s fascinating stuff. Along the way, your team develops skills - one might be good wading through the water, another might be good at catching thrown objects, say - and find items that make things a little less brutal. Snuff? A shield perhaps? A full meal? How kind. Progress was slow for me, particularly at first, but Gods Will Fall worships at the shrine of Katamari in the end - kill one god and you become that much more likely to Beowulf your way through the next one and the one after. That said, stupid mistakes, coupled with plenty of opportunities to lob yourself into space and die, will keep you grounded. And besides, the story, such as it is, your story, the patchwork story of this run and the next, is constantly shifting beneath you. I love Gods Will Fall the most when an unexpected death confers an unexpected stat boost that makes for an unexpected champion. At such moments the story bucks and resettles the way myths and sagas must have bucked and resettled in the endless retelling. Fate is no longer a dice roll. It’s the needle and thread that dips and dances through the tapestry.